the building blocks of accounting

Debits and credits (abbreviated as Dr and Cr respectively) refer to entries made in a double entry accounting system to record transactions and increase or decrease account balances accordingly. In a double entry system debits and credits must always balance each other out, and every transaction must be recorded with at least one debit and one equal credit. This means that every transaction a business makes, regardless of complexity, can be boiled down to a series of simple debits and credits, and because of this principle, debits and credits can be referred to as the building blocks of accounting.

In order to properly understand the nuances of debits and credits, we must first understand what an account actually is in a business accounting system, and we must also understand the difference between “double entry” and “single entry” accounting.

What is an account?

In simple terms, an account is just a category label for transactions. Expense accounts represent various types of business expenses such as phone, internet, rent, utilities, etc. Asset accounts represent various business assets such as vehicles, machinery, equipment, buildings, etc. When a business accounting system is set up, the company must identify the accounts that are most relevant to the business and list them out in something called the “Chart of Accounts” or “COA” for short. At a fundamental level, the chart of accounts is simply a list of all the various categories a business uses to sort its transactions.

It is important to note that the term “account” in an accounting system does not always reference a physical account with a tangible balance like a checking or savings account. For example, an expense account titled “Rent Expense” would not reference any physical account, it exists to track the total amount of rent the business has paid during a given accounting period.

There are many different accounts (and subaccounts) in a proper double entry system, however, these accounts can generally be rounded up into 5 basic account types and two separate account classes.

The two classes of accounts are:

- Balance Sheet Accounts

- These are the accounts that appear on a company’s balance sheet

- They include Assets such as bank accounts, cash, vehicles, etc. Liabilities such as loans and credit cards, and Owners Equity accounts.

- Income Statement Accounts

- These are the accounts that appear on a company’s income statement (or P&L).

- These include all the various Revenue and Expense accounts.

The 5 basic account types are:

- Assets

- Cash & equivalents, vehicles, machinery, equipment, land, buildings, etc.

- Liabilities

- Debts payable by the company. Unearned revenue/customer deposits. Accrued expenses.

- Equity

- Contributions and withdrawals made by owners

- Revenue

- Earned income from sales.

- Expenses

- COGS: inventory, raw materials, direct labor costs, etc.

- Overhead expenses: SG&A payroll, rent, utilities, phone, internet, software subscriptions, marketing, etc.

Double Entry vs. Single Entry

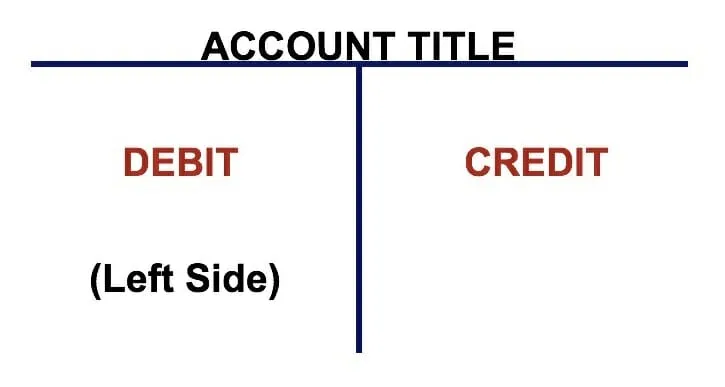

Enter the T-Chart

Accounts in a double entry system can be visualized as T-Charts with the left side being the debit column and the right side being the credit column. See the image below for reference:

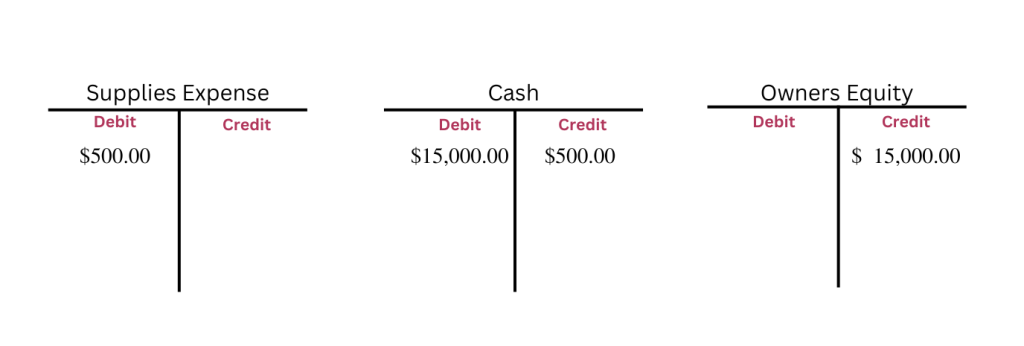

When transactions are recorded in a journal entry, the corresponding debits and credits are added to the appropriate columns of each account affected by the transaction. For example, if a company purchases supplies for $500 in cash, the transaction results in a decrease to “Cash” and an increase to “Supplies Expense”. In this scenario you’d record the journal entry as: Dr – “Supplies Expense”, Cr – “Cash”.

Once the journal entry is recorded, you will add the debit from the journal entry to the debit column (left side) of the “Supplies Expense” account and the credit from the journal entry to the credit column (right side) of the “Cash” account in the general ledger. Computerized systems will automatically do this and calculate the resulting balances for you, however, pretending we’re in 1962 and doing everything with pen and paper, it would look like this:

From there, we can calculate the balance of each account by taking the sum of all the debits in the debit column and subtracting it by the sum of all the credits in the credit column (or vice versa depending on which column ends up having the larger value). In this scenario, since there’s only one transaction affecting each account, the calculation is simple. We can calculate that “Supplies Expense” has a debit balance of $500 and “Cash” has a credit balance of $500.

This doesn’t really tell us anything though, until we understand what a “normal balance” is and which accounts should be debited and credited.

What is a Normal Balance?

Where our “Cash” account has a previous debit balance of $15,000 resulting from an initial investment made by the business owner. We’ve included a third account titled “Owners Equity” with a credit balance of $15,000 to illustrate the other side of this transaction. In this scenario, “Supplies Expense” still has a debit balance of $500, but our “Cash” account now also has a debit balance of $14,500, showing that we started with $15,000 (debit), spent $500 (credit), and still have $14,500 leftover.

when to use debits and when to use credits??

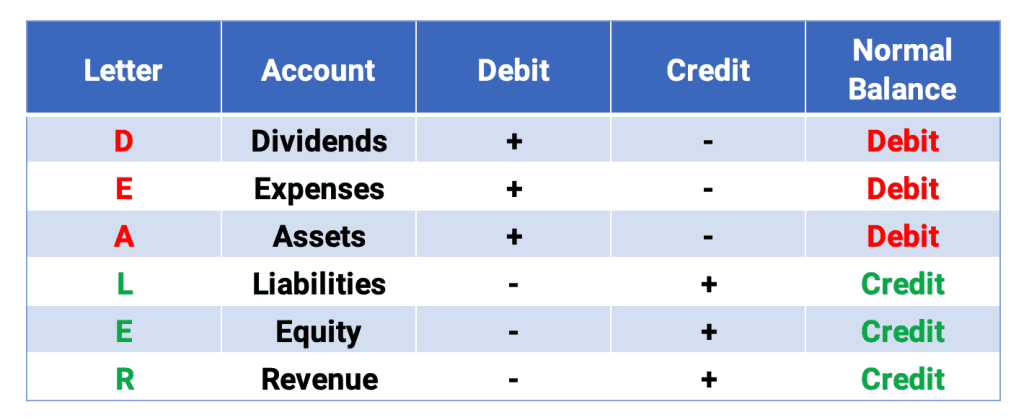

This is a very confusing concept to grasp for most beginners. It’s hard enough to understand all the various account types, let alone their normal balances and when to debit them or when to credit them. My advice, and what clicked for me during my first year of college is to use the “DEALER” method to remember the normal balance of the most common account types.

DEALER is an acronym that stands for:

- Dividends

- Expenses

- Assets

- Liabilities

- Equity

- Revenue

Shoutout to finallylearn.com for this image (url: https://finallylearn.com/debits-and-credits-explained-illustrated-guide/#What-are-debits-and-credits)

The first three account types in the DEALER acronym all have normal debit balances and the last 3 all have normal credit balances. Any time you need to record a transaction, you’ll want to consider which accounts are being affected, and then evaluate which category the accounts fall under this acronym. This will give you a solid idea of which account to debit to and which account to credit.

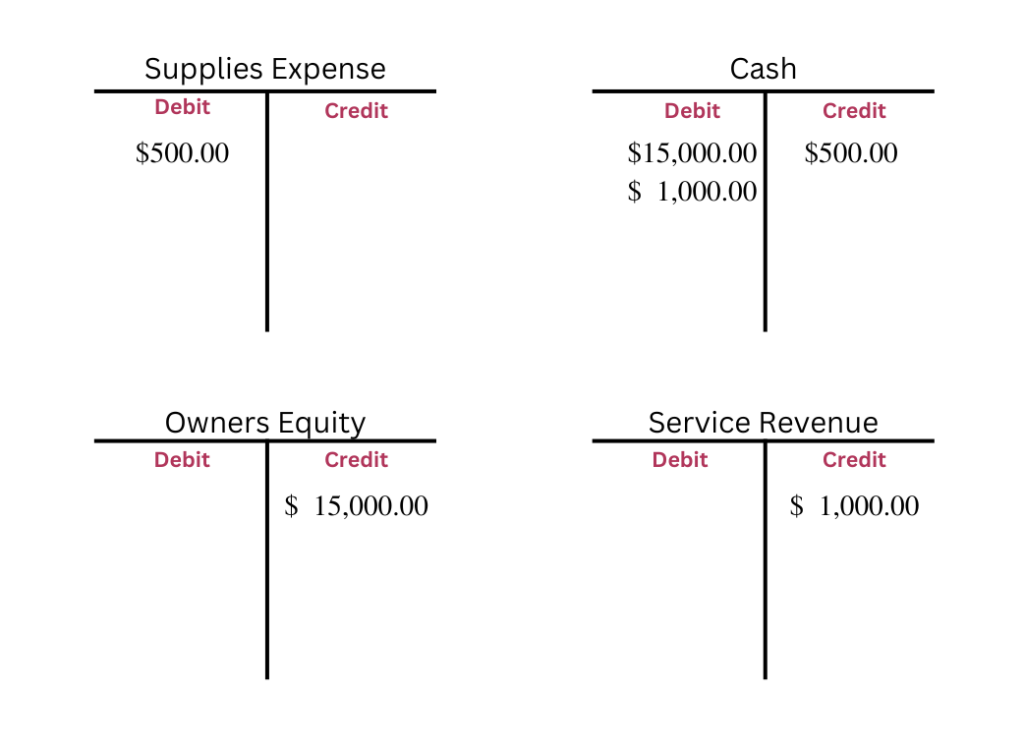

For example, lets say our business sells a service for $1,000. In order to record the transaction, we want to first examine what exactly is taking place here and which accounts are affected. We’re making a sale, which means we’re receiving $1,000 in revenue, and this revenue is going to be added to our “Cash” account. Looking at it like this, we’ve identified that the two accounts that are affected by this transaction are “Cash” and “Service Revenue”. Next we’ll want to determine how these accounts are going to be impacted. We’re receiving $1,000 which means our revenue has increased, this $1,000 is then added to our “Cash” account, which means our cash has also increased. Knowing this, when we record the transaction we want to apply debits and credits appropriately to increase both “Cash” and “Service Revenue”.

From here, we can take a look at the DEALER acronym to see where we should place the debits and credits. We know that “Cash” is an asset, so according to the DEALER method, we need to apply a debit to increase this account. The DEALER method also tells us that in order to increase “Revenue” accounts we need to apply a credit. We know that each transaction in a double entry system should consist of at least one debit and one equal credit, so in this case the resulting journal entry is simple.

According to the DEALER method, we need to make a $1000 debit to “Cash” and a $1000 credit to “Service Revenue”. Upon recording the journal entry in a computerized system, the affected accounts will automatically update and their account balances will be adjusted accordingly. The resulting T-Charts would look like this:

As you can see it gets more complicated as transactions flow through the system and new accounts come into play. For the sake of this article though, we’re simply focusing on the relationship between debits and credits. As you can see above, our new “Cash” account balance is $15,500, showing that we started with a $15,000 investment, spent $500 on supplies, and then generated $1000 in service revenue.

Why does it work this way?

Frankly, because some very smart people decided it should a long time ago. The concept of why certain accounts have normal debit balances and why others have normal credit balances is an arbitrary one and has a lot to do with the way the accounting formula works and how the various accounts interact with each other. I personally wasted way too much time in my intro to accounting class trying to wrap my head around why revenue increases with a credit and why cash increases with a debit, when in reality asking that question is like asking why Y=MX+B… The best answer I can give you as a beginner is that it just does. It’s not really important to understand why at first, and as you learn more about accounting and start to understand the larger picture, it’ll all make a lot more sense.

If debits increase assets, then why do banks credit your account to increase it?

This is something that confuses a lot of people who are new to accounting. You’ve likely gone your entire adult life understanding the terms “Credit” to mean an increase and “Debit” to mean a decrease because that’s how all the banks word it, and they aren’t necessarily wrong. The disconnect here is because people fail to realize that banks are speaking from their own perspective, not your perspective as the customer.

When you deposit $100 into your bank account, think about what happens on the back end at the bank. They’re receiving $100 which increases their assets, so they have to record a Debit to their “Cash” account, but this $100 doesn’t belong to them. It’s your money, not theirs, so they wouldn’t record it as revenue. They have to be able to pay this money back to you whenever you request it. In this sense, it’s almost like you’re giving the bank a loan of $100. And we know that loans are liability accounts, and liabilities have normal credit balances.

So when you deposit $100 at the bank, the transaction is recorded on the bank side as a $100 debit to “Cash” and a $100 credit to the liability account they have set up for you as a customer. This is why the banks use the term “credit” when they refer to money going into your account. It’s because your checking/savings account balance is a liability to the bank, and we know (thanks to the DEALER method) that credits increase liabilities.

Where can i go to learn more?

Aside from poking around our own blog, we recommend you check out accountingcoach.com. It’s a great FREE course to learn all about the basics of accounting. They offer self paced modules, practice tests, and various certificates for completion. This is one of the best free resources available, however, there is no shortage of paid courses you can take on platforms like Udemy. Just be sure you’re taking high-quality courses with good reviews.

Unlike most subjects, I actually don’t recommend trying to learn accounting on your own through YouTube videos or blog posts like this one. This sort of content can be a great refresher or a helpful addition to structured course material, but to really grasp the concepts of accounting you’ll likely have better luck taking an actual course.